‘Concept art’ is a useful umbrella term, but it doesn’t capture how expansive a field it is. Within Atomhawk alone, we house so many specialisations that are classed as concept art. Our character and environment teams have multiple sub-disciplines in each, and our creatives have many directions to hone their artistic and technical skills in. Each discipline has real depths of expertise to master.

We follow an ‘artist first’ approach, which informs every piece of work we create. This means we make a direct connection between high quality creative output and artists who are empowered and supported in their day-to-day work, and their long-term career goals. This ethos is foundational to our way of working.

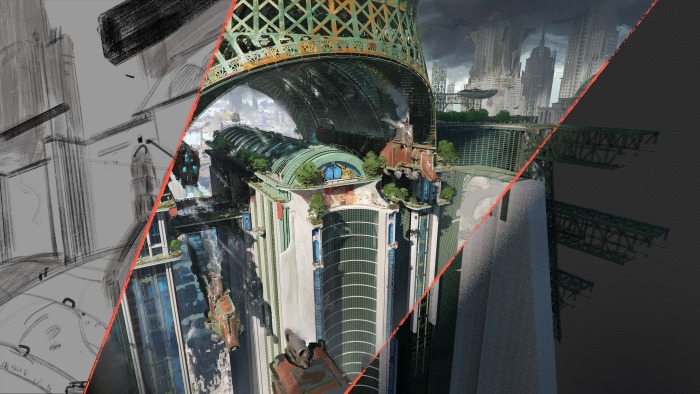

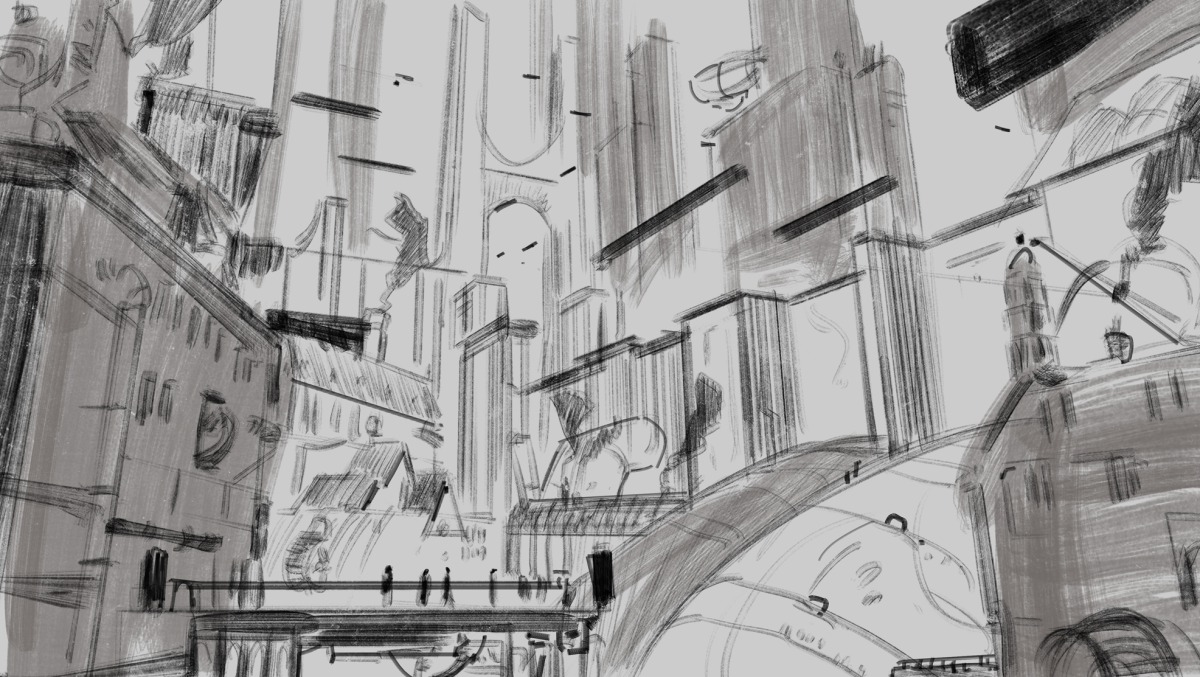

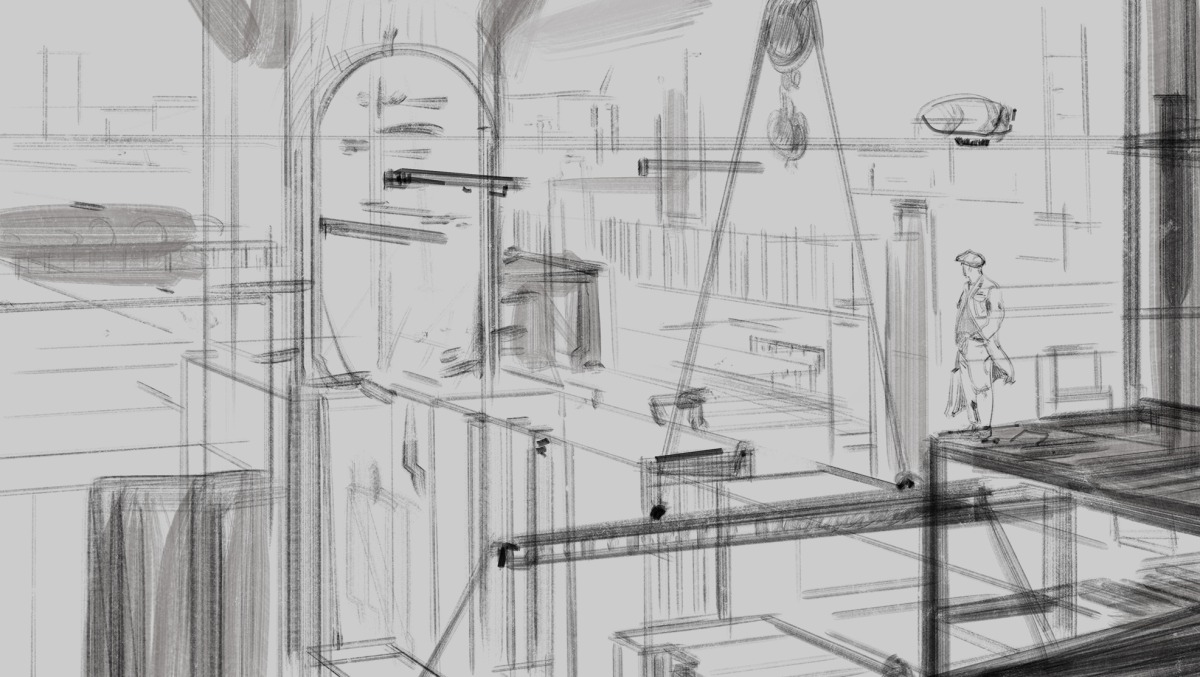

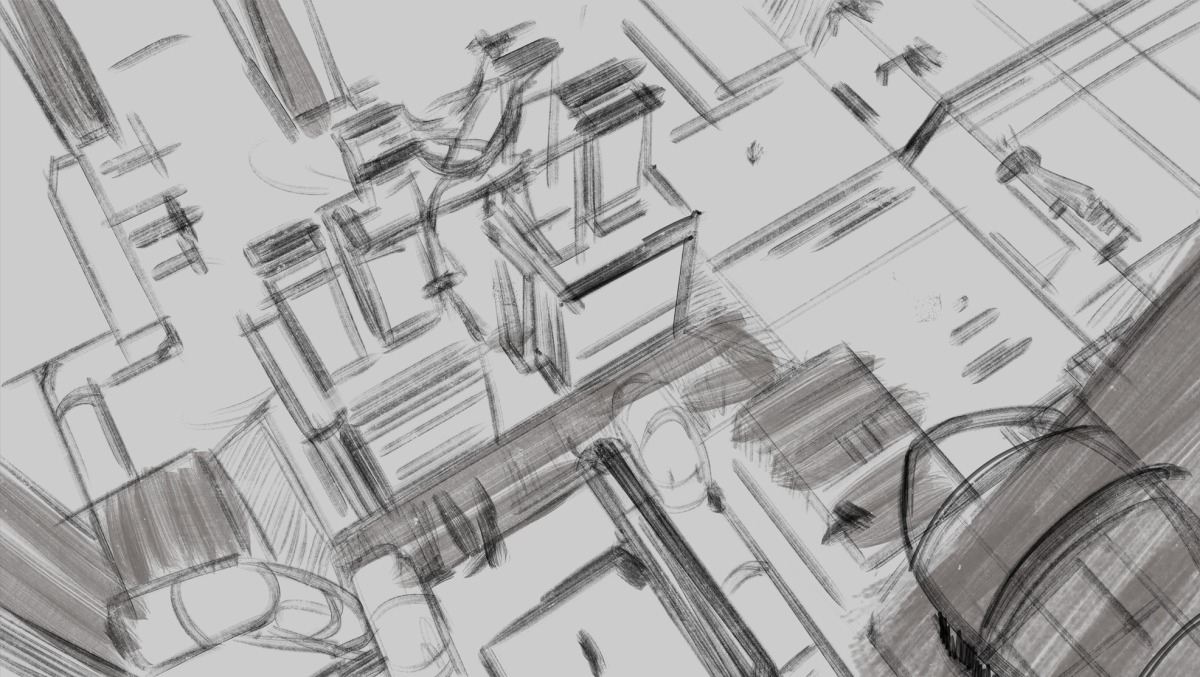

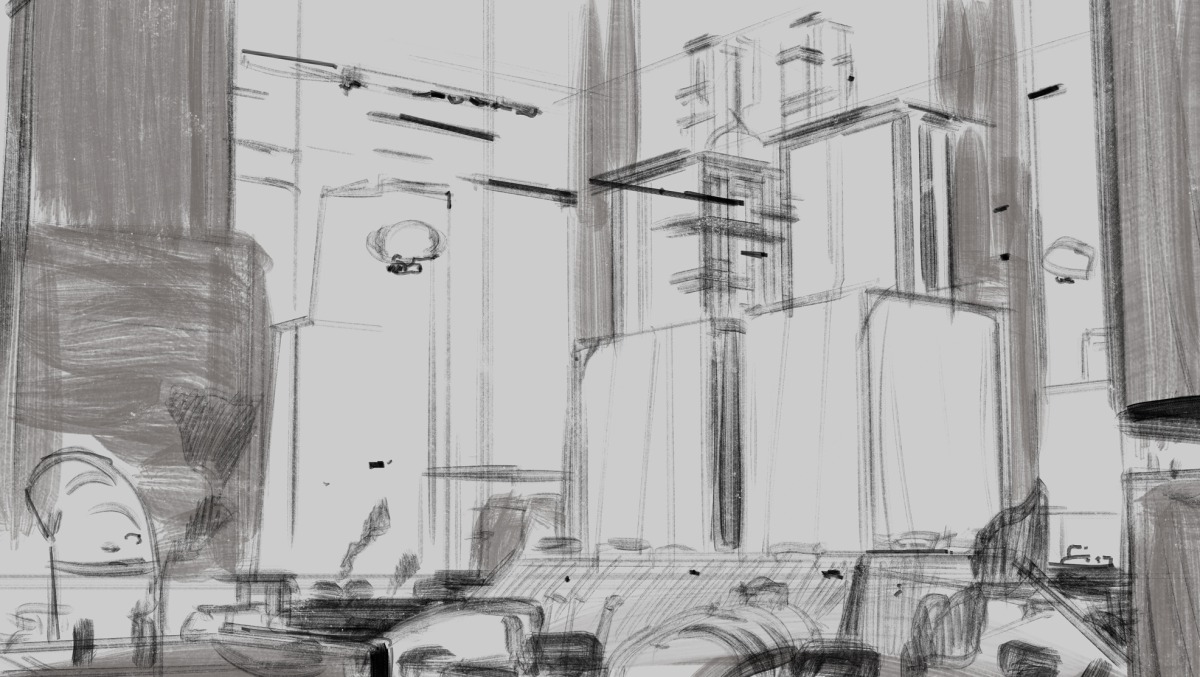

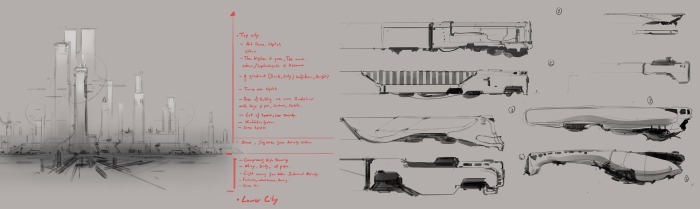

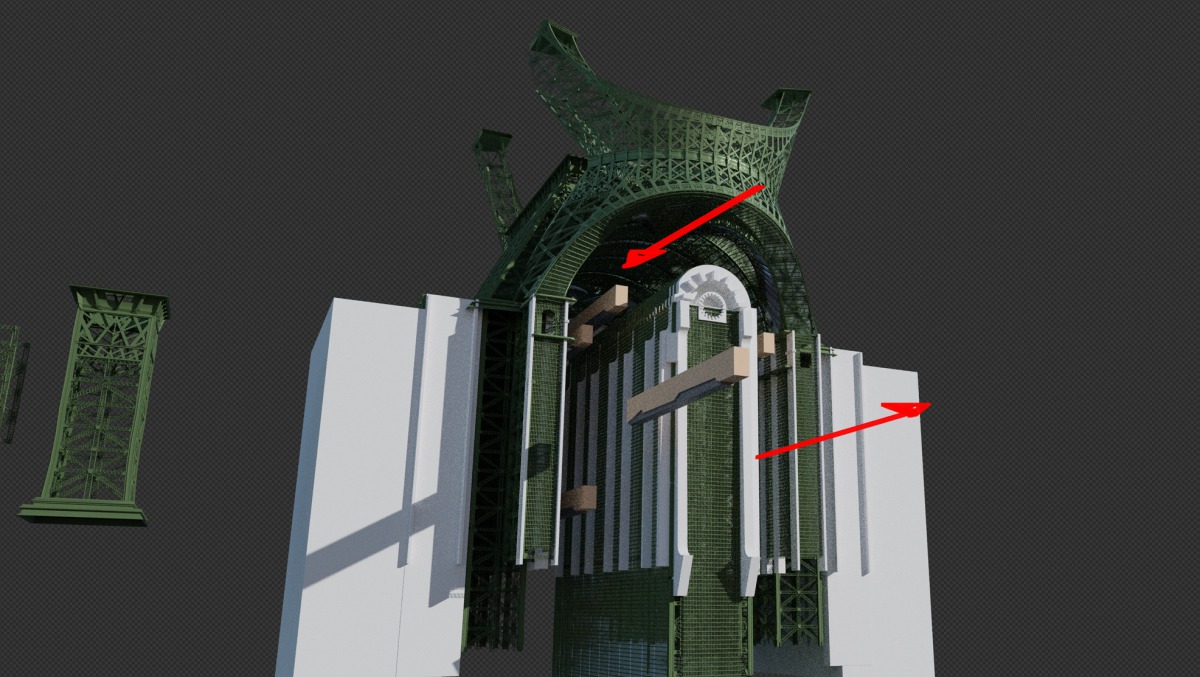

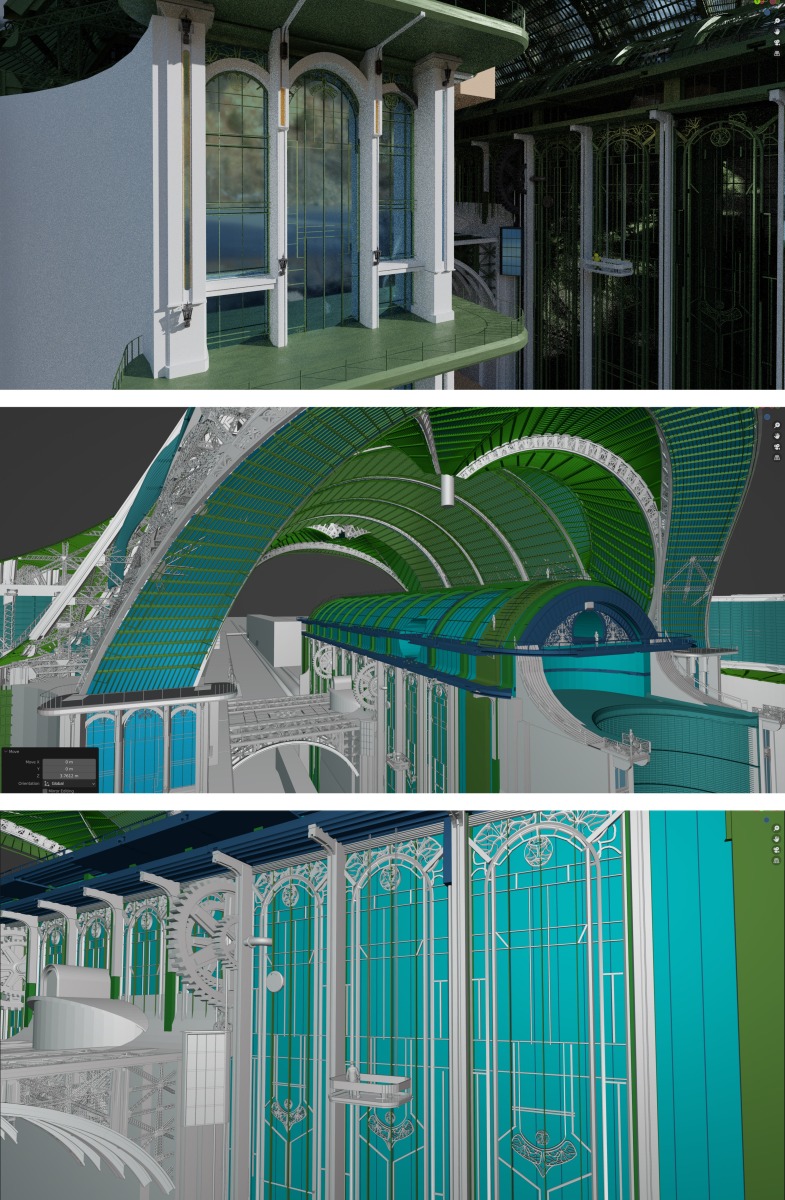

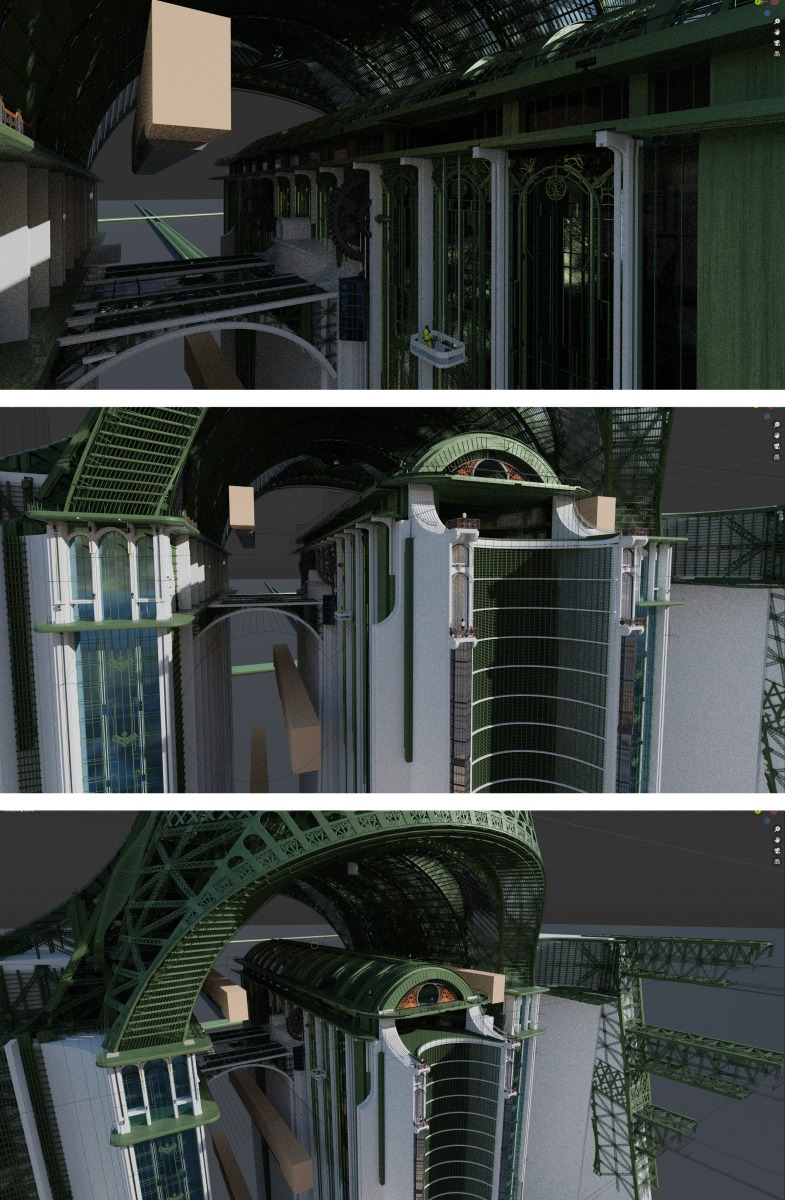

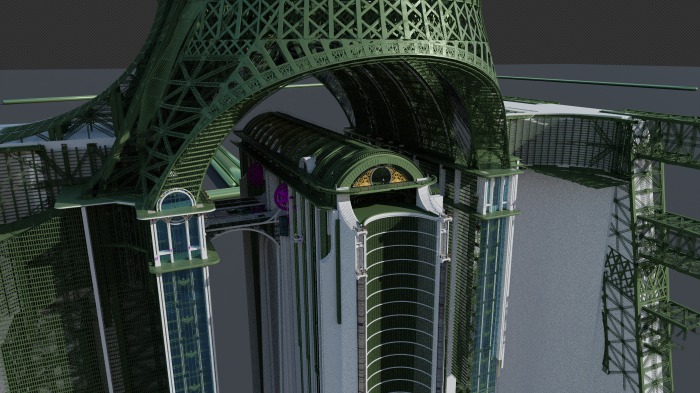

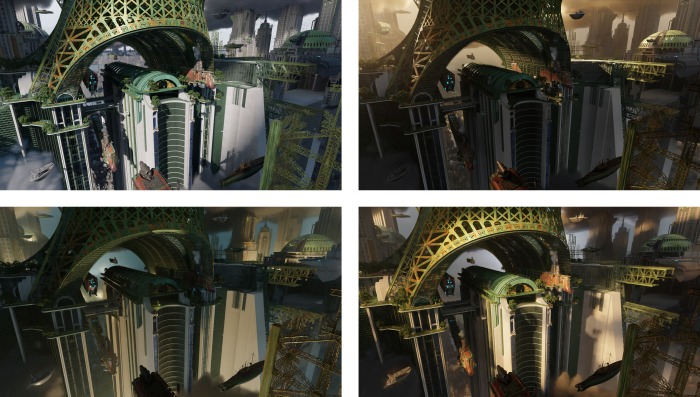

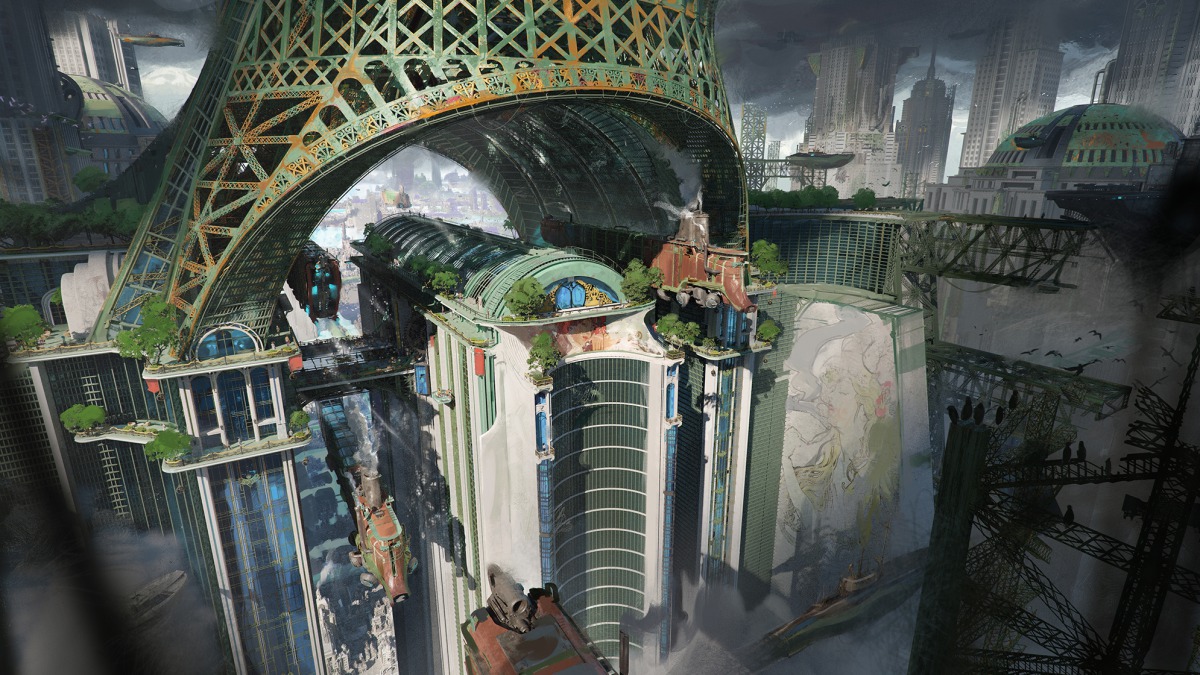

Today, we’re focusing on Environment Art, with Louis Laurent, Lead Environment Artist from Atomhawk Canada. He’s taken the time to lead us step-by-step through how he created this intricate and imposing steel edifice.